Government can do amazing things

Wales. Image by Steffan Mitchell (Unsplash)

One of the major critiques of politics and politicians is the short-term nature of the election cycle and the short term nature of political visions and decisions. There are a lot of different ways to address this — from banning corporate donations, to extending the electoral cycle, to increasing lobbyist transparency, etc.

Caernarfon, Wales. Photo by Mick Haupt (Unsplash)

But what I’m most excited about at the moment is the idea of a Future Generations Commissioner.

Recently I attended the John Menadue Oration hosted by the Centre for Policy Development. The speaker was Sophie Howe, the outgoing Welsh Future Generations Commissioner, with a compelling presentation on what it looks like to put wellbeing at the heart of government decision making. And to be honest, she blew my socks off.

Wales might be a small country, but jeez they’re leading the way in what might be possible.

Before I get into the details of what they’re achieving, let's back up and talk about what the Future Generations Commissioner role actually is, and what the job involves.

As Howe tells it, her role as the Commissioner was to be a coach, mentor and the legislated “conscience of future generations”. She was mandated to call out the madness of short-term thinking, hold the hands of those trying to do things differently, and to speak out when decisions seemed to be being made that might go against the interests of future generations. Howe’s role was all about hope, inspiration and leadership – with the backing of not only the government and the law (her position is baked into the Future Generations Act), but broader Welsh society.

It's hard to imagine how someone like this could actually have much power. After all we already have many commissioner roles, such as a National Children’s Commissioner, a Disability Services Commissioner, and a Sex Discrimination Commissioner, commissioners for women, etc. But in Australia at least, their ability to have an impact is siloed.

What makes Howe’s position different is that she works across issues and isn’t boxed into one particular topic area and, importantly, she is guided by the seven wellbeing goals developed by involving the Welsh population.

In 2014/15 the Welsh Government supported a process to develop and grow a national conversation on ‘The Wales We Want’. The Welsh people were invited to participate in conversations, send in ideas and submissions (via surveys, videos, reports, postcards or drawings) and to own the process as much as possible. (It seems not dissimilar to the Australian Kitchen Table Conversations that fuelled Indi in regional Victoria, and then other electorates around the country, to elect community-minded independents.) Local areas started to have localised conversations as regions and towns asked not just what they wanted for Wales as a whole, but what they wanted at a more localised level as well.

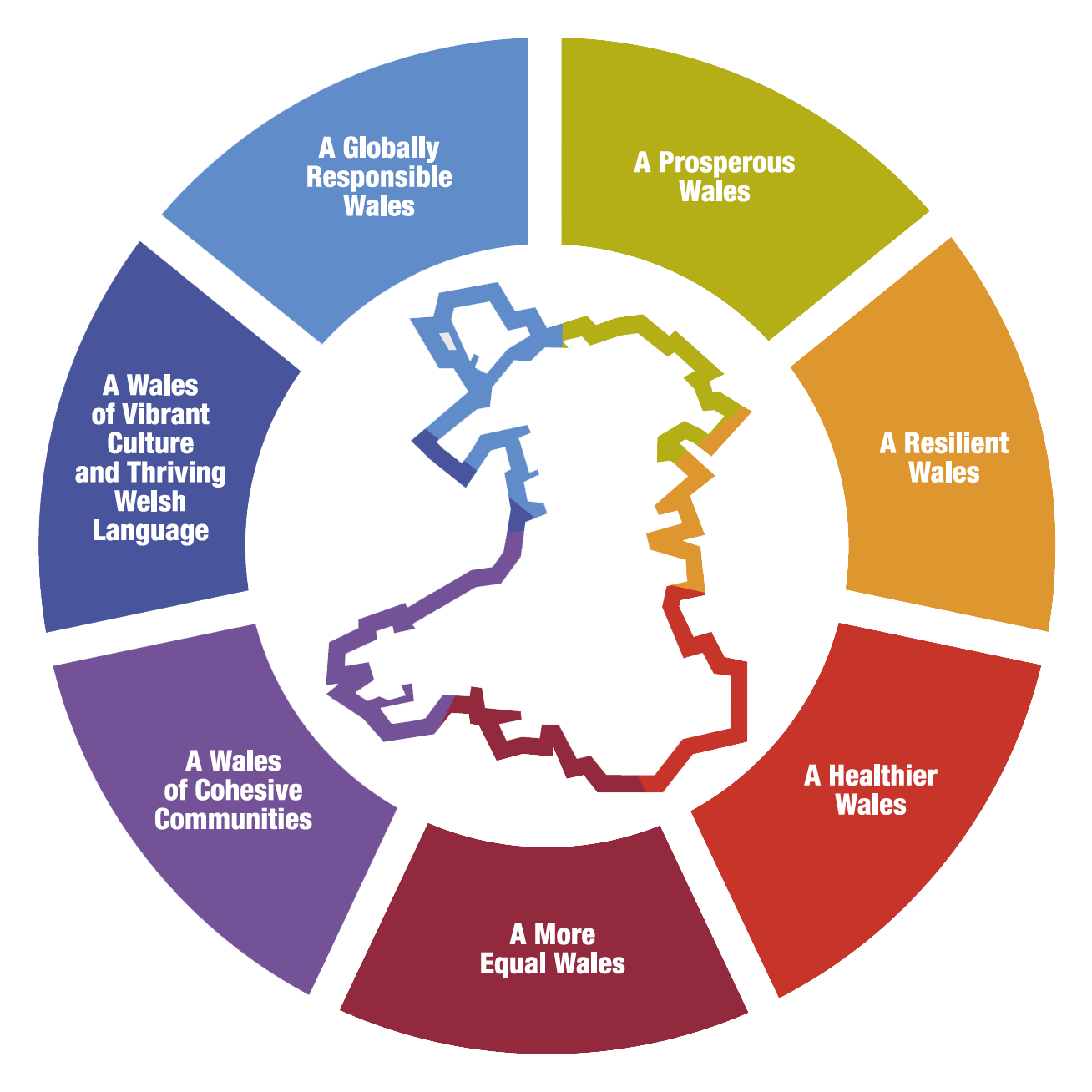

The upshot of this process was the development of the seven wellbeing goals, which are now enshrined in Welsh law:

The Seven Wellbeing Goals (source: Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015)

A prosperous Wales

A resilient Wales

A healthier Wales

A more equal Wales

A Wales of cohesive communities

A Wales of vibrant culture and thriving Welsh language

A globally responsible Wales

It’s well worth checking out the details of these goals over at the Future Commissioner website.

As Howe tells it, about 10,000 people participated in this process – pretty good going for a country of just over 3 million people!

What I find particularly powerful and inspiring here is that while business and community sectors have their place, the role of the public sector is front and centre in keeping the country focussed on these goals —and ensuring their conditions for success — with some unorthodox approaches.

Llandudno, Wales. Photo by Aydin Hassan (Unsplash)

Howe talked about how achieving a healthy Wales was never going to be done simply by boosting spending in healthcare, for example. She pointed out that if you combined all the healthcare systems in the world and pretended they were a country, their combined total climate emissions would be the fifth largest in the world. Which is problematic really isn't it, when you consider the impacts of climate change on health!

Instead, Wales looked to research from the World Health Organisation which says that only 10% of the inequality in health status in Europe is due to health services, compared to income security (35%), living conditions (29%), and social capital (eg, the strength of people’s sense of connection and belonging) (19%). They realised that addressing health issues requires working across silos and thinking about the upstream conditions. I love this!

So now, the Welsh government has begun procuring local post offices as a part of its health plan. They recognised that local community service hubs, such as post offices, are important places for people to work, gather and access services locally. Seems weird until you realise that social capital and maintaining the social fabric is not only a wellbeing goal in itself, but it’s inherently tied to health outcomes for the community.

What a brilliant way of conceiving of the role of the public sector and how it might serve the public good!

Another example of expanded thinking around health was the hospital that didn’t sell its surplus land to developers, and instead used the Future Generations Act to make the case that the land should be used for community-grown food and space to restore and connect with nature. Yet another hospital hosts the first hospital-based solar farm in the UK, reducing some of those carbon emissions.

What they’ve been able to achieve overall in Wales in the last seven years is truly astounding and inspiring. They’ve effectively put a freeze on all new roads — finding new more holistic approaches including massive investment in public transport and prioritising more walkable communities. They’ve worked with schools to create a curriculum focussed on wellbeing and climate action. They have the third highest recycling rate in the world (even using recycled nappies as road base!). Most importantly, I think, Wales now has a completely new way of measuring success: from short-term GDP to long-term wellbeing.

Cardiff, Wales. Image by Taylor Floyd Mews (Unsplash)

So many of the case studies on the website show increases in local community engagement and control, with schools and community centres taking the lead. What’s important though, is this is backed and resourced by the Welsh Government, making acting locally something that is relevant and connected up to the bigger national picture.

Of course, it’s not all been smooth or easy.

There are gaps between aspiration and outcome, as particularly the social sectors struggle for the resources needed to make the changes required. Howe acknowledged this herself, saying that a lot of her work had been in unravelling old ways of doing things: noting things like it's all very well to require long term planning but that means nothing if funding is annual. Similarly, you can’t expect innovation and not allow time and space for failure.

Other critiques are that the process is too slow and that the Act lacks real teeth to protect important community assets. What matters of course is how these critiques are acted on by the government. Changing the way a country measures progress is a massive shift and one that takes time. As with any big project, regular reviews and public transparency about successes and failures are essential, as is a budget on the scale that matches the ambition! The last thing we need is a project that “wellbeing washes” business as usual.

Implications for Australia

It strikes me that in Australia, the time is ripe for this type of legislated articulation of wellbeing goals. We’ve got the Labor government moving towards a wellbeing budget and a citizenry energised and excited by Kitchen Table conversations and enthusiasm for democratic participation. At the same time, the Australian Public Service is undergoing a reform process with an eye to clarifying and articulating a “strong purpose and clear values and principles,” which means policy makers may be open to new approaches. The idea of a Future Generations Commissioner ticks many boxes here: it involves the public, it's a fresh new politics for the federal government, and it gives bureaucratic form and power to holistic thinking at a national level.

The challenge of course is making it happen.

Photo by Pat Whelan (Unsplash)

The way it happened in Wales was that the Environment Minister thought it was a good idea. But then another minister from a different area thought it should be in their portfolio too, and then another — while people in sectors outside government wanted to be involved too. It became a far bigger project – all the better!

In her oration, Howe reflected on the essential nature of not just ‘engaging’ or ‘consulting’ but actively involving community in the creation of the purpose statement.

I’ve been a qualitative researcher for nearly 20 years now and I’ve seen the power of not just asking people about their problems, but the incredible energy and sense of collective purpose that occurs when you ask about possibilities. The nine pillars of Australia reMADE are an example of how despite political, social, economic, geographic and cultural differences across the country, we ultimately share the same vision and values. Truly, in the work I’ve done listening to people talk about their vision for Australia or what public goods they want for themselves and their communities, I’ve heard far more similarities than differences. And while we’ve captured these visions and values in the nine pillars and the 3Cs (care, connection, contribution — from our work into the public good), what’s more important is the process.

The process of involvement and the process of visioning together are essential for long term support, buy-in and ownership from the public if we’re ever to have anything like a Future Generations Act. Our public good work has shown that people are eager to contribute to the bigger national story, they’re keen to be genuinely heard and to offer their perspectives, skills and enthusiasm. They want to feel that big sense of belonging to a greater collective purpose.

Imagine if something like 'the Australia we want' was nationally developed, agreed upon and enshrined into legislation. Imagine if every policy and program had to consider whether it contributed to these goals.

And imagine if we had someone in the position of Commissioner for Future Generations — responsible to support, cajole, encourage (and re-courage) and hold a country to account for its impact on future generations and the public good.

What could we make happen?

DR MILLIE ROONEY

Millie is a Co-Director for Australia reMADE. She has a qualitative research background and has spoken in-depth with hundreds of Australian's about their lives, communities and dreams. Millie is also a carer for her family and community and is passionate about acknowledging this work as a valid, valuable and legitimate use of her time.

SELECTED OTHER BLOGS BY MILLIE: