Three Things I've Learned from Toni Hassan

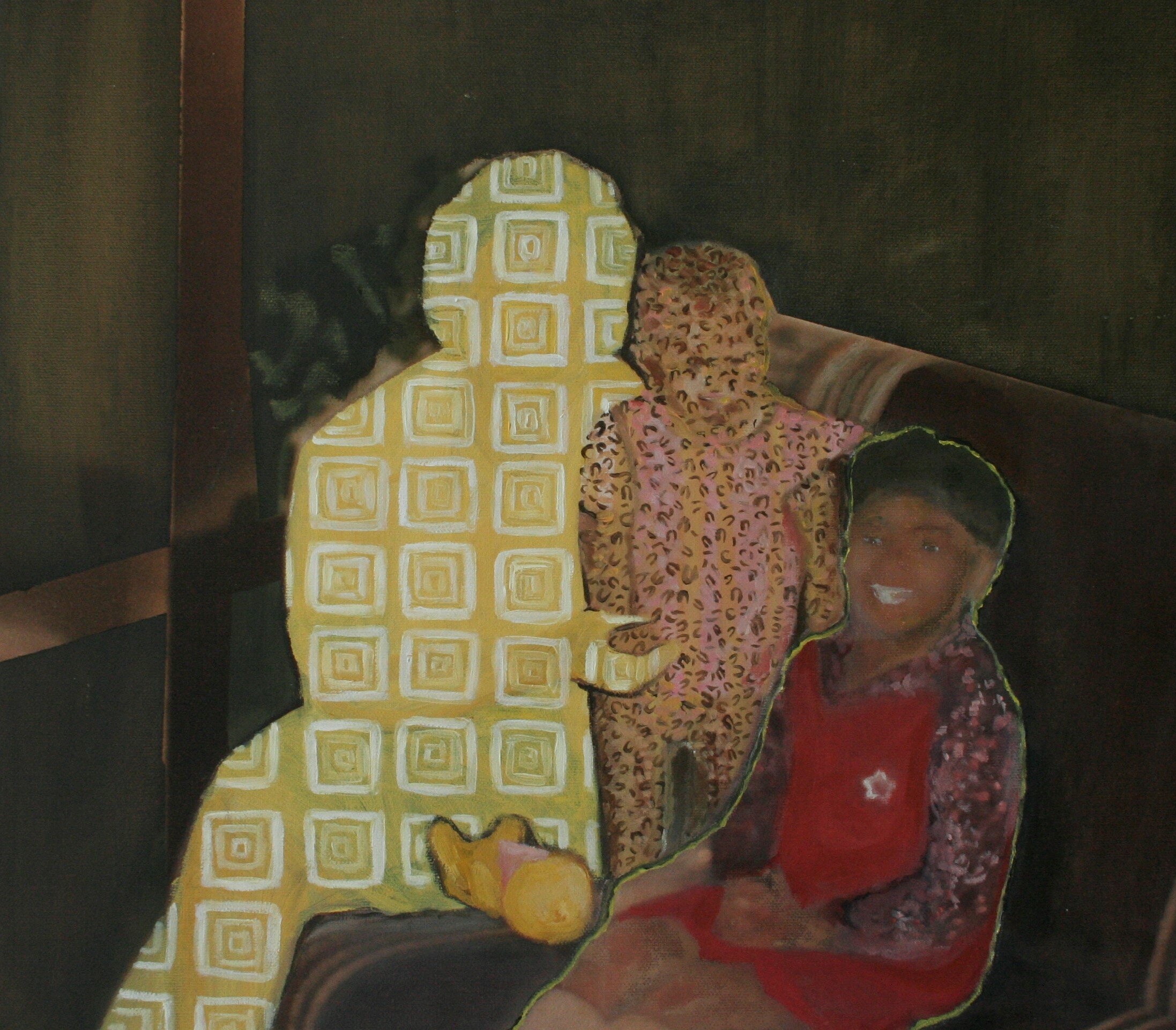

Toni Hassan. "The patterns we adopt" Oil and acrylic on canvas board, 42 x 47cm (displayed with the artist’s permission).

Listen to our conversation with Toni over at the reMAKERS

It’s a slightly intimidating privilege to interview a woman who’s spent her career asking the questions. Toni Hassan is a Walkley-award winning journalist, author, visual artist and parent. Her book, Families in the Digital Age, is a guide for parents navigating the complexities of these tech-heavy times, as well as call-to-arms for all of us to reclaim our attention and intention within our wild and precious lives.

Firstly, you should know that Toni’s worldview is informed by Christian teachings, the legacy of apartheid, and much time spent listening. She strikes me as someone who takes her work seriously, but holds herself with humility and humour. (“Living in a city like Canberra you realise you know nothing!” she says. “It’s a very intense, earnest city full of PhDs.”)

What also struck me about Toni, beyond the dulcet tones and articulate nature of her radio-trained voice, was her rich capacity to weave together complex, seemingly disparate ideas into a singular inviting form…the perfect woollen jumper you longed to make your own. So having been fortunate to enjoy a wise and wide-ranging conversation with her and Millie, I wanted to share at least a smidgen. Here are three things I’ve learned from Toni Hassan.

“The greatest currency or asset we have is our attention, is our capacity to be truly present, to be with people, to sit with them in the mud.” - Toni Hassan, the reMAKERS podcast Season 2, episode 8.

1. Phones have become our new sacred objects, and the ‘rituals’ they create aren’t healthy.

Estimates vary wildly, but recent studies report the average person checks their smartphone anywhere between 85 and 344 times per day. Often it’s first thing in the morning, last thing at night and every few minutes in between. Articles about screen addiction have become commonplace: it’s the ‘tool’ that’s using us; the content we’re meant to engage in as empowered readers, co-creators and consumers — that has us feeling consumed.

“What the phone does is it ritualises our lives in ways we know aren’t good for us, but we go back there,” says Toni.

Image credit: Priscilla Du Preez

I had thought plenty about screen addiction, but not about phones as our new sacred objects (just try leaving yours in the other room for a while), ritualising our lives in ways we don’t fully intend.

Of course navigating this is a challenge for everyone, but it’s especially poignant for those of us currently raising children.

“We risk being benignly negligent because of the tyranny of the urgent,” Toni says.

That’s not to heap blame or guilt on parents. Every email, every text, every notification is designed to feel immediate. They pull us away from the moment and the people we’re with, so that we can easily feel inadequate for not responding right away.

Toni also reflects on how the digital space also invites our young people, who are still working out who they are, to perform and present themselves in particular ways.

“It’s quite straight-jacketed, it’s prescribed, there are commercial forces.”

And she says something seismic is going on with young people as a result. “Children and young people are experiencing unusually high levels of anxiety, and it’s, ‘I’m always on’, and [it’s] the phenomena of what’s known as the intermittent reward system at work.”

Toni’s invitation to all of us is to actively resist, pull back and create alternative rituals that both nourish us and build community. She gives her tips on where to start as individuals, and we also talk about the kinds of solutions we need to explore as a collective in order to remake technology to better serve the public good.

2. Systems often feel inevitable and impossible to change in the present, and obviously flawed and fixable once in the rearview mirror.

Toni’s parents left South Africa for Australia in the 1970s, and a key reason was to get away from apartheid. She grew up grappling with the legacy of a system so obviously flawed and manufactured, that it prompted a lifelong interest in understanding both the visible and invisible systems of power: “the way they can either create space for us to thrive, equip us to be the people we wish to be, or diminish us”.

Image credit: Hunter James

“Apartheid, like no other political system, helps us see how the law is manufactured. Legislation passed by parliaments and in fact the courts are constructs. They reflect the stories we’ve ourselves or have been told to us. They reflect a values system, they reflect a belief system,” she says.

It is easy to look back on a system of power like apartheid and see that there was nothing ‘natural’ or inevitable about it. But what about the systems we’re part of today? How often do we ask, ‘who is this designed to serve, and who is it harming? What is its purpose, and are we still happy with that?’

We drew connections back to that most powerful of modern forces, Big Tech. Toni is currently engaged in an argument with the ACT Education Directorate over the mandatory introduction of Google Chromebooks from year 7, potentially even younger. “They’re thinking about rolling it out amongst preschoolers. It’s absurd! There’s no evidence for that.”

“It’s left to those of us who care to have a conversation about what we dream of, the natural limits of Big Tech, what it is we could do,” she says. “It’s about having honest conversations about what it is we know, and asking our representatives in Parliament to help us understand, and then building alternatives.”

We are living in a time of great disruption and rapid transformation. So we need to keep asking, ‘who is this serving, who is it harming, what is its purpose and are we still happy with that?’

Toni’s story and perspective remind me that even the most pervasive, seemingly all-powerful systems can be transformed, surprisingly quickly. To paraphrase Nelson Mandela: it’s always seemed impossible, until it’s done.

3. “I can make, and in making have agency.”

Okay I’ll admit straight off the top to my own feelings of clumsiness and incompetence when it comes to ‘the arts’. I do not see myself as visually creative. I am not crafty. I do not sew. But whenever I’ve been game enough to get over myself and try, I’ve found the process of making things, small things, invites a level of irrational joy.

Toni asks, ‘what can you do that really gets you in material, whether it be clay or pastels?’ She talks about a dad she observed who was so embarrassed that his daughter had gotten paint on a chair at childcare that he joked, ‘this is why we use the iPad to paint at home.’

“Let children be children!” Toni implores. “Give them spaces to play, to make mess. To play with plasticine, to explore the material world in places that are safe.”

Image credit: Ricardo Viana

Psychologists, philosophers, coaches and even neuroscientists have much to say about why we humans need to do more than passively consume in order to be truly well. It was such an obvious thing and practical necessity for most of human history that it’s kind of amazing that we now need to relearn its importance.

“We are on hyper alert all the time, adding to our sense of anxiety,” Toni reflects. “The non-digital and low-tech arts creates space for therapeutic practice, where you are able to play with colour or the texture of clay in your hands. You’re able to forget yourself to gain yourself. It’s precious time to help create space… I definitely encourage, it doesn't have to take over your life, but arts and crafts that fit you.”

Toni also talks about how the arts can give us the public space to process our private feelings in shared ways. She uses art to process her deep lament about a changing climate, for example.

“You do the painting of someone surviving floods in northern NSW, and then it becomes the talking point. The public finishes the work, the work is completed by the viewer.”

These private feelings that we’re all carrying need opportunities to be processed in shared ways, “but not with the metronome of the news, and the anxiety the news generates,” she says.

In the days since our chat I haven’t found complete inner peace or creative self-actualisation. I haven’t managed to get to any concerts, or to our local art gallery to share publicly in expressions of love, rage, lament or beauty. But I have found myself softening, slowing down, remembering to pause and exercise my agency over the rituals that I allow into my life. I’ve tried to notice the delight, rather than the mess, when my children create at home. And I’ve tried to remember that this whole big shebang is a collective work in progress, not a private challenge to overcome alone.

As Millie says to Toni, “much of your work can be summed up as: ‘remember there’s a world out there!’” Thank goodness.

For the full interview and show notes, click here or find the reMAKERS wherever you listen to podcasts. You can buy Toni’s book here.

LILIAN SPENCER

Lilian Spencer is the Communications Lead for Australia reMADE. She believes that the secret to change is to, ‘focus your energy not on fighting the old, but on building the new.’

Selected Other blogs by LILY:

If a tree falls in your front yard, who comes to clean it up?

What is our why? Reclaiming our sense of purpose as a country