The recovery begins now

We will come out of this pandemic a different country – the question is how different and who decides.

Are we in a hiatus that returns us to business-as-usual or is this a pivot point to something better?

It is a contest about which values win out long term: cooperation over competition, society over the economy, a thriving democracy over an authoritarian state... people and planet first?

To win that debate we need ideas that excite and inspire people. We also need ideas and policies that will transform the very drivers that shape our world.

This document is a contribution to developing the tools and frameworks that will help us in this work.

As ambitious as it is imperfect we felt the urgent need to start somewhere!

April 2020

The times we live in

Feeling a bit like a yo-yo? Suspect you’re not alone!

There’s the depths: the coffins, the fear, the isolation, the unemployment queues, the distant loved ones, the people without running water…

Then there’s the uplift: the million acts of giving, sharing and supporting; old communities rediscovered and new ones created; the health and aged care staff literally putting their lives on the line; the birds you can hear as the traffic noise dissipates; the air you can breathe deeply…

Our politics feels a bit the same as we swing from the highs and the lows to the wins and the worries.

So yes, quite an emotional roller coaster.

And just like the bushfires, COVID-19 is drowning out most everything else. There is no other issue, no other news. Frustrating for campaigners everywhere – particularly as we watch the climate clock ticking down. But for all the noise it also weirdly feels like being in a state of suspended animation.

The big question for us all is, what’s next?

It feels uncomfortable to talk about ‘what’s next’ when we know there’s still much pain and loss to be experienced, but being prepared for what happens post the pandemic needs to start now. The critical question is whether this period becomes a hiatus, ‘an interruption in time or continuity?’ Or does it become a critical inflection point, a pivot, ‘on which something turns?’

All the many epitaphs being penned currently for neoliberalism – for the belief that the bogey of the deficit has gone, that the righteous value of public infrastructure has been resurrected forevermore and that we are all now society-first aficionados – presuppose we are at an inevitable pivot point. One that will see the recovery from this crisis chart a course fundamentally different to the neoliberal decades that preceded it.

But we could just as easily slide back to that well-travelled path. This could just be a hiatus – after which life continues on with the same individualist profit-motive values and economy-first focus. Only it won't really be the same: rather we could well see a doubling down on all those old neoliberal tropes about debt being bad, the unemployed being less worthy and the public sector being too big. Overlay that with a swaggering attitude to surveillance and control by the state and the hiatus has the potential to become a pivot to something much scarier.

These ideas have always been contested, but in this period of contradiction and flux never more so.

The difference this time is that we have a national community that has lived through the shock and brutality of our bushfire summer, followed closely by this ‘unprecedented’ experience of a lifetime.

People’s material experience, the financial and emotional scarring, the community bonding, and the deep appreciation for place, for local support and for public services has never been more to the fore in public consciousness.

Our capacity to engage and create a social force out of this heightened consciousness will be key to how we resolve this contest for the future of the world we face.

The future we desire

Naomi Klein’s exhortation that ‘No is Not Enough’ is key in this next period. Critique by itself is too depressing. A critique will not win hearts and minds and move agendas. A vision will.

At the heart of Australia reMADE is the notion of public good: of a country where the needs of people and planet come before the wants of markets and money.

The Australia reMADE vision is made up of nine pillars and envisions a world where, among other things, we achieve “First Peoples’ full control over decisions impacting lives and communities,” “free access to clean air and water, to good food and to land that is well cared for” and “a government that delivers the things ordinary people care most about… [like] education, health, transport and other essential services”. A country where, “paid jobs have dignity and workers have rights” and we can “live full and meaningful lives in and out of the workplace,” and “have good public infrastructure such as transport, parks and gardens…”

This was a vision developed across many communities and resonated despite circumstance. It is beautiful and inspiring, it animates and motivates.

But it is not enough on its own.

We need to take this to the next level. How do we make this vision a reality?

The temptation is to fall back onto lists! Lists of policies for every issue. And yes, at some point we will need policies and even lists.

But what we need first, goes deeper. This vision will only be born through sifting and shifting key foundational values and the drivers that give them expression. Too often we ‘play on the surface’ and fail to appreciate and therefore focus on changing the drivers that create the problems in the first place.

Transformative change – change that creates new value norms and different types of drivers – is key.

Identifying the key drivers of transformation

Where to start?

As with most of Australia reMADE’s work we end up doing a jig between ‘the unravelling’ (trying to work out how things are built or connected) and ‘remaking’ (looking at what is required for transformation).

Although there is a lot of talk about neoliberalism – the key ideology that has shaped much of how capitalism has operated over the last 40-50 years – it is worth trying to synthesise some of its key elements to unravel the drivers at work.

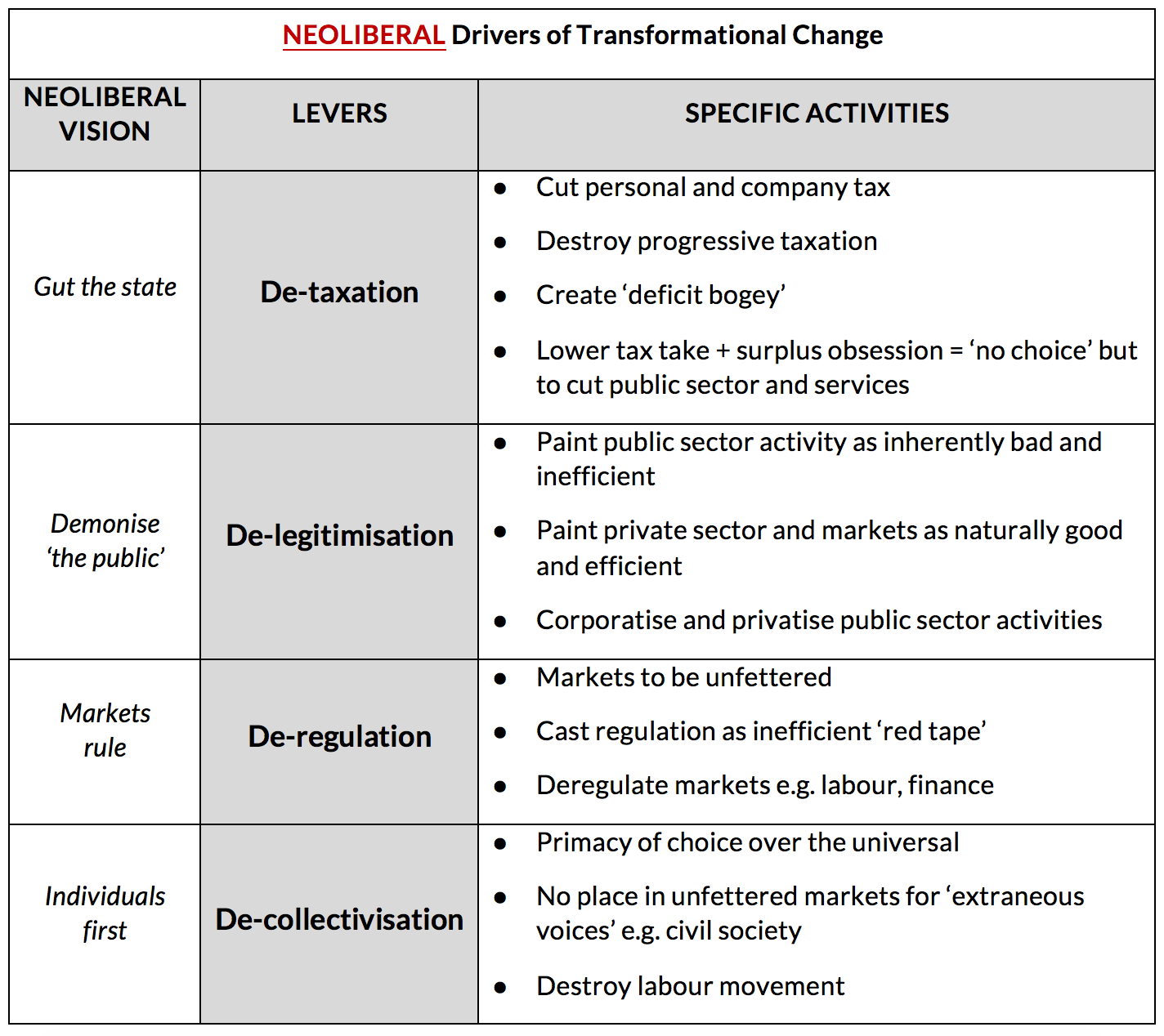

This table highlights some of the key drivers used to deliver the neoliberal ideal:

These neoliberal tropes have been highly successful and are very deeply embedded – almost reflexively so – in the structuring of how things work and in how many people think.

But the underlying values that animate the Australia reMADE vision are very different. These include:

Shifting to the front foot

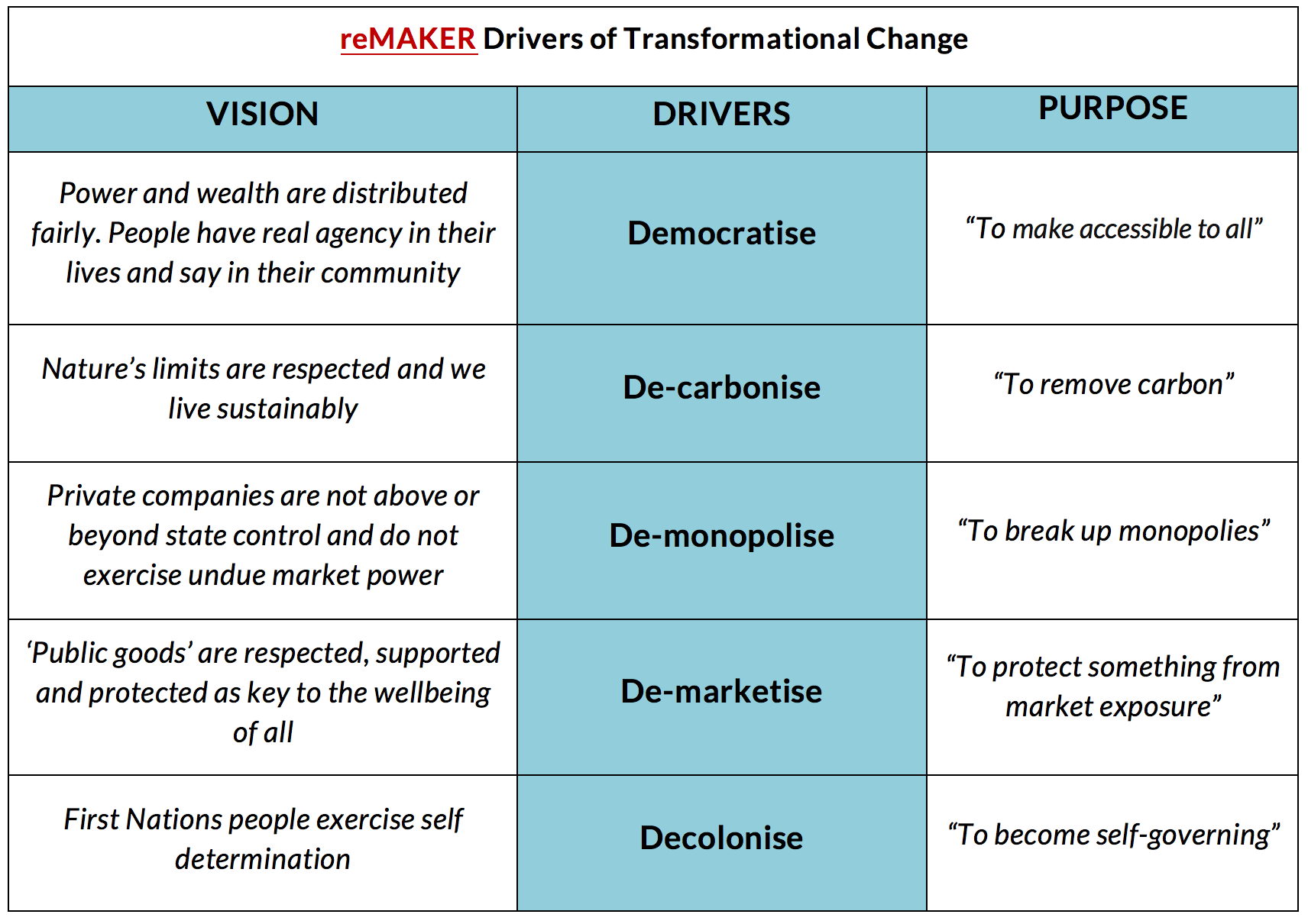

We have had a go at trying to pull together our own framework of transformational drivers, rooted in the ambition of Australia reMADE. This is very much a work in progress that will only improve with further rigorous consideration and discussion. So please treat it as such – a first go!

So how might this help?

Below we begin to unpack democratise, de-monopolise and de-marketise. Please note there is a process in place, coordinated by CANA (the Climate Action Network of Australia) looking at what deeper work is required to de-carbonise and so this paper doesn’t attempt to preempt this work. Similarly, there are processes amongst First Nations people to identify their priorities as regards decolonise and again we await their proposals.

Take Democratise

We have intentionally chosen ‘democratise’ the verb rather than ‘democracy’ the noun, on the basis that a flourishing democracy can only operate if we get the democratise bit right. And there are two key elements to democratise:

1. How we ‘balance things better’ in terms of power and wealth

‘Balancing’ means that in order to give people genuine access to power and decision-making, to opportunities and rights, to services and activities, we need to increase equality.

We need to ‘get money out of politics’ – that means measures like real time transparency and caps on donations, expenditure caps on election spends and public registers for lobbyists. But even then, even with all the good regulation in the world, money speaks. When there is an imbalance in society and a few can disproportionately drown out the voices of the many, something has to change. Bottomline: a healthy democracy relies on a fairer distribution of wealth and power across the community.

How do we develop ideas that genuinely shift wealth and power?

We could repurpose corporations – e.g. how might we do away with or better regulate unchecked buybacks, ludicrous executive pay, continued shareholder primacy, the externalising of environmental and social impacts, outdated patent laws or excessive mark-ups and profits?

Or we could decide that we don’t want lots of multi-millionaires or billionaires in Australia and design our tax system accordingly e.g. removing the privileging of capital income over wages, regulating trusts and tax havens, etc.

Well those couple of prompts have got a few hares running!

They may not be the best, the most judicious, the most possible or the most effective policy routes to be exploring. The central question we are posing here is that ‘to democratise’ – to allow all Australians equitable access to ‘things’ – including that democracy ‘thing’ – there needs to be better balance in the sharing of wealth and power in this country.

The momentum for some time has been toward a greater concentration at the top end of the wealth scale. So it isn’t even as if we’re in a neutral position. Transformational change to the key drivers that allow wealth to accumulate in this way need to be rethought… that is if we genuinely want to democratise and ultimately bolster and sustain a healthy viable democracy.

2. How we ‘create genuine engagement’

Removing the power imbalance is key but so too is re-imagining how people engage and decide. That is partly why we talk of the need to ‘democratise’ not just of democracy itself. Narrowly prescribed representative democracy insufficiently fits the many ways people can and do engage, decide and act.

If ever we wanted to be reminded of the importance of local connection and organisation, the bushfires were a vivid reminder. Now is the time to rethink how to reinvigorate or reinvent processes and structures in ways that genuinely encourage and support all Australians to be part of public decision-making.

Take De-monopolise

De-monopolise focuses on reducing, dismantling or offsetting concentrations of corporate power as they impact the operation of the economy and our democracy. We identify two elements to this:

1. Reducing concentrated corporate power in the market

While the neoliberal mantra says that efficient markets require competition, domestic and global markets for many industries are best characterised as oligopolies and virtual monopolies. In Australia they represent half the profits of the top 200 ASX listed companies.

This type of concentrated market power comes at a price – constraint of innovation, reduction of new entrants, price collusion, choice reduction, wage suppression and supply chain squeeze to name a few. And as we move into a period of climate shocks and the need to regear our economy can we trust these juggernauts to be sufficiently nimble?

There is also the concern that dominant corporations are increasingly shaping our lives. Amazon has seen-off many of our independent book stores and publishers, and increasingly determines which books we read. A couple of entertainment corporations pretty much determine what our kids see and hear on TV. Companies like Monsanto-Bayer basically determine how farmers farm across the globe. Where’s the mandate, the accountability and the limits on such power?

Covid-19 also forces a reflection on how reliant the world’s ‘self-isolatees’ are on just a handful of IT and Comms behemoths. Risky much?

The other feature of the pandemic is that while many businesses have been forced to close, some like Amazon are going gangbusters. We should consider an emergency (excess profits) tax on those profiting from this crisis. It’s been done in war times – and it is a recognition that their capacity to even be operating is due to the trillions of public dollars being spent to bolster lives and livelihoods.

2. Reducing concentrated corporate power in our democracy:

Another way to constrain the power of concentrated market players is to ensure there are countervailing forces. We need to rehabilitate the public right to expose, oppose, organise and advocate. Too often we silo these rights – workers’ rights, charities’ freedom to advocate, greenies’ right to campaign, journalists’ right to protect their sources – defining each as distinct and special.

Rather we should be re-imagining the creation of a set of public rights that ensure those with aggregated power are accountable and subject to community concerns; while those taking on the accounting are respected and protected.

Take De-marketise

It seems so innocuous to suggest that there are things we might want to protect from market exposure, yet this is absolute heresy under neoliberalism where everything from the individual to the state must be exposed to market forces.

De-marketise is partly about identifying new ground that might need new protections from market incursion or control (like privacy, or online communications) but also about recouping lost ground – particularly around things we would regard as more traditional ‘public goods’ such as spaces, services, rights, infrastructure, etc.

So the key elements we have identified so far relating to de-marketise are:

1. Protecting and reinstating public goods

From an Australia reMADE perspective, creating the public good means making decisions that benefit people and planet before money and markets. In light of the Australian community’s experience of both the bushfires and the coronavirus, there is potential for a very exciting and dynamic community conversation around notions of public goods and reclaiming of the public good ideal from the overly simplistic notion that what is good for the economy is good for the people.

A conversation that unpacks what being the best version of us looks like, where we identify the social and economic safety net below which no Australian falls, where a new appreciation for nature and place is reflected – these are just some of the public goods we want to re-imagine.

2. Protecting and reinstating public goods

We’ve seen the increasing creep of privatisation of publicly provided goods and services such as health, welfare (cashless debit cards anyone?), water, energy and more. In some instances the transferal from public provision for the public good to private provision for private profit is obvious (such as the selling off in the 90s of Telstra, the Commonwealth Bank, Qantas, airports, railways and some state electricity generation). In other instances, the shift to privatisation is more subtle in the form of public private partnerships, voucher systems, competitive processes for civil society funding and service delivery etc. We need to develop criteria for determining which public goods should not be in private hands; and which require at least some degree of public control. There are fantastic examples globally to inspire us.

3. Protecting the funding base for public goods

While governments hide behind ‘deficits are bad’, ‘tax cuts are good’, and ‘the family budget and national budget operate the same’ there will be problems with protecting a secure funding base for public goods. We need to remember that funding public goods is a choice – it's more about priorities than imaginary fiscal constraints.

4. Choosing how public goods are best delivered

Public goods do not always have to be controlled and delivered by the state. Having the conversation about how public goods are managed is going to be as important as our understanding of public goods themselves. Options might include open source collective processes, cooperatives at various scales, local government control, or certain types of public/private partnerships. There are fantastic examples around the world of each of these approaches delivering public goods. The bottom line is that we shouldn’t just assume that there is a one size fits all solution – particularly if we are looking to also deliver on our ambition to democratise and create new pathways for people to engage in broader decision-making.

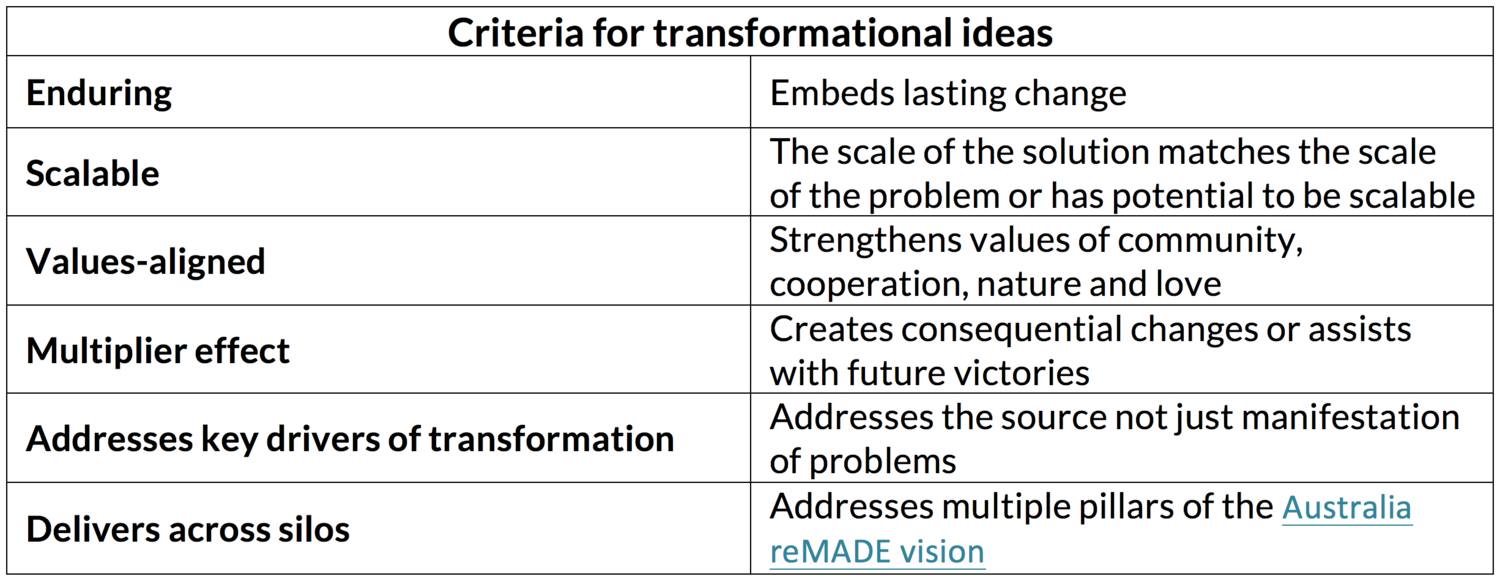

Criteria for assessing the transformational capacity of Big Ideas

For each of the Levers identified there are any number of possible policy options – and some haven’t even been thought of as yet.

We have had a go at developing some criteria (or prompts) to help assess and shape those options. For example:

How do we assess one idea over another?

How do we think about the architecture of ideas – for example what makes one version of the Universal Basic Income (UBI) potentially acceptable butanother problematic?

How do we constantly push ourselves to ‘imagine more’ – to open our thinking to be bigger and bolder?

The following list doesn’t mean every policy has to do everything!

It is meant to be a tool to assist and, like the rest of these frameworks, is open to further discussion and adaptation.

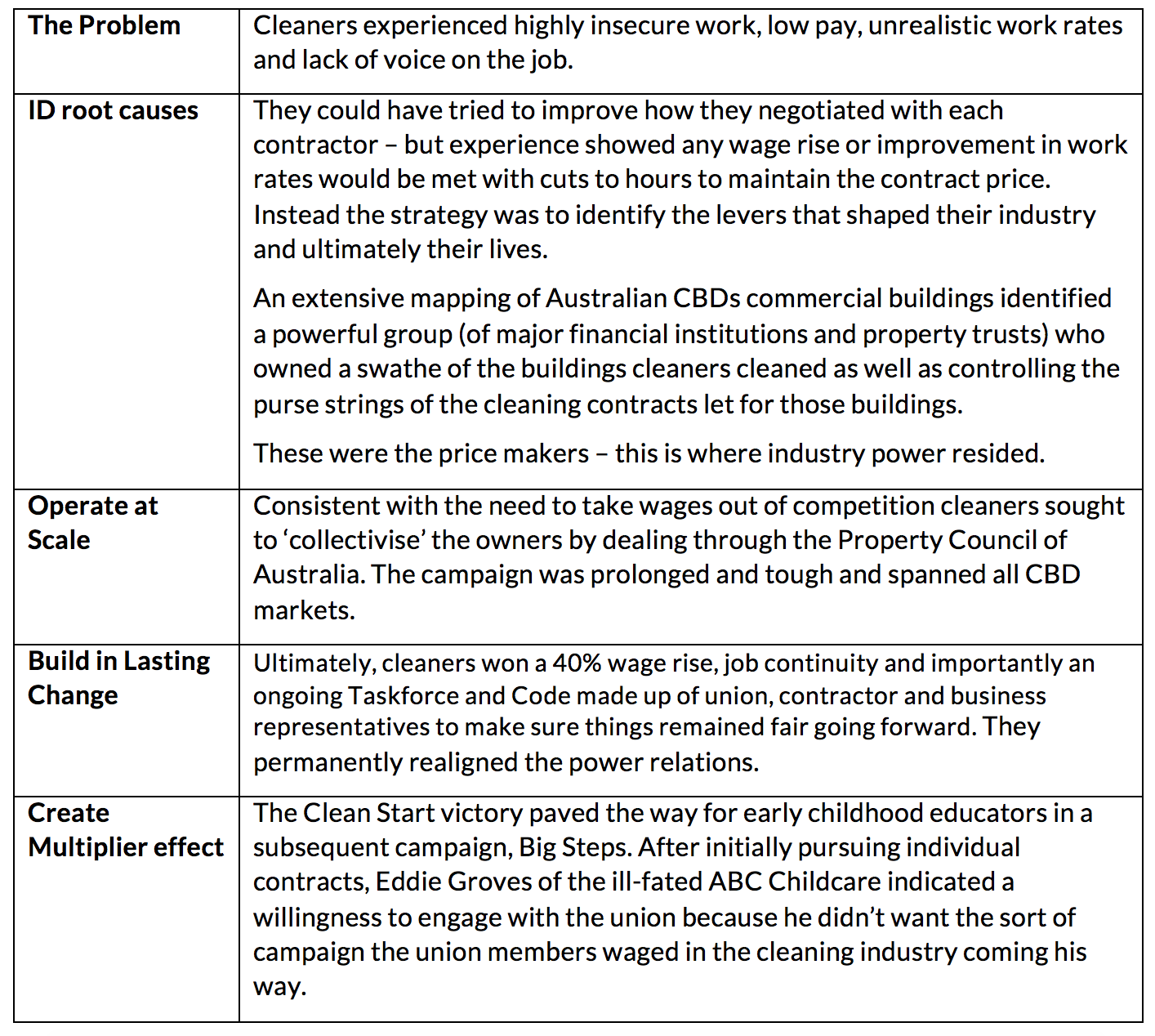

A case study: Low paid Cleaners show how it is possible

It is always easier to envisage these things through example. A good one comes from the early 2000s, from the Clean Start campaign, involving cleaning members of the United Workers Union (then United Voice).

To recap

We’re living in yo-yo times, and what happens next is not a foregone conclusion.

We need more than just another critique of all the bad things happening and we need to do more than simply fight to hold onto the gains won in this period. Both are essential but not sufficient if we are to use this generational moment to transform and reMAKE Australia.

Wishful thinking won’t get us there. Hence our attempt at helping us to think about transformational change – how we shift the values foundation; how we shift the levers that actualise those values in systems, policies, institutions and budgets; and how we critique and nudge our own thinking to be bold, ambitious and focused on root causes. About the need to democratise, de-carbonise, de-monopolise, de-marketise and decolonise.

Ambitious much? But that is what the moment calls for.

Go gently on us, we’re learning as we go!

Now, next and beyond

What now, what next, what beyond? If it seems too soon to be talking about life after the pandemic, or too impossible to keep all these different balls in the air at once, take heart. None of this is easy, and we’re all in unchartered territory.

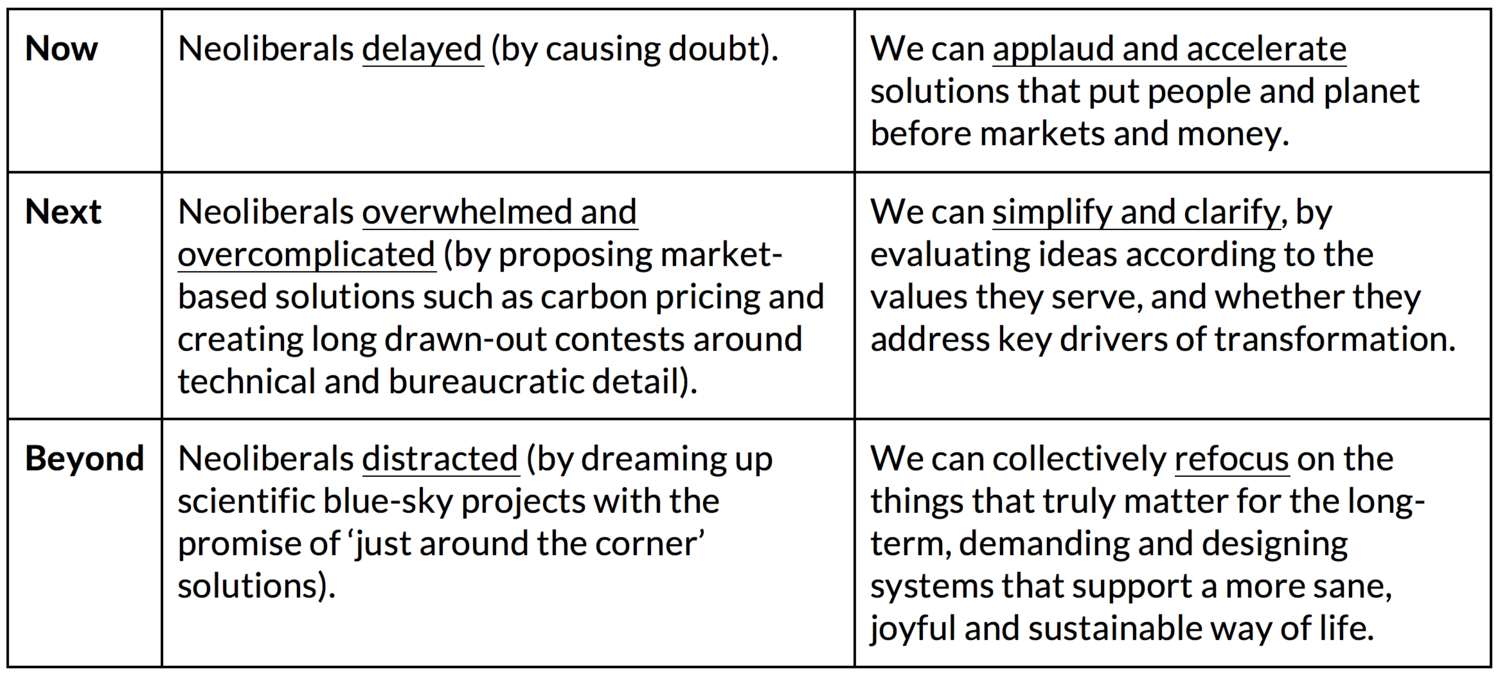

Many have compared the rapid, no-holds-barred global response to COVID-19 to the slow, meagre half-measures taken to stop damage to our climate. But here again, we can actually study and learn from the old neoliberal playbook.

For decades now, neoliberals have had no real answer (or intent) to stop climate change.

How might we invert this to shape what comes next for the better?

Mapping a future that we can embrace will require us to feel a little vulnerable. Then again, how vulnerable can it really feel putting forward bold ideas for debate once we’ve survived a global pandemic?

The upside

Having now experienced two back-to-back crises of epic proportions, we Australians will share a dramatically reduced tolerance for bullshit. The old ideological battle lines will continue to seem especially useless in the face of long unemployment queues and industries collapsing. The idea that the ‘free market’ should rule over all will seem entirely laughable in the face of huge bailouts, public works programs and ongoing wage subsidies. The idea that government itself is largely a game that’s about ‘winning’ things for your side and ‘beating’ down the other side will strike us as utterly obscene. And while permanent paradigm shifts aren’t guaranteed, nor is it written that we must rush back to an old ‘normal’ that fundamentally does not serve us.

“The challenge, for nations as for individuals in crisis, is to figure out which parts of their identities are already functioning well and don’t need changing, and which parts are no longer working and do need changing.” - Jared Diamond, Upheaval: Turning Points for Nations in Crisis.

We have already learned some very good things in these turbulent times. Things we can’t unlearn: like when faced with an existential threat, we really will spend any amount of money to protect one another. Like ‘there really is such a thing as a society’. Now our job is to take these lessons into the reconstruction, and discard that which needs changing. We will come out of this pandemic a different country. The question is how different, and who decides.

The Australia reMADE team